Political leadership comes in different forms. Even focussing very narrowly on the American left, Elizabeth Warren has spent her career building technical regulatory solutions to consumer problems such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, whereas Bernie Sanders’ appeal has been advocating big, transformative ideas, building strong public support for policies such as a Green New Deal. In a sense Sanders’ leadership is similar to Theodore Roosevelt’s idea of a high-profile role as a “bully pulpit”.

Historically the Green Party of England and Wales has had a flatter, more consensus-based leadership structure than other parties, having Male and Female Principle Speakers between 1992 and 2008. Notable Principle Speakers included Caroline Lucas, Sian Berry, and Derek Wall. An academic and historian of ecosocialism, Wall was against the switch to a Leader and Deputy Leaders, arguing “Leaders provide an easy target for manipulation by the corporations and often manipulate members to make their parties less radical, evoking short-term electoral gain.”

But even under the Leader model the Green Party is more decentralised than other parties. In part this is because the Leader and Deputies are only elected for a limited term (normally two years, one year on this occasion because of a delay necessitated by last year’s general election). Sian Berry decided not to re-stand as co-leader in 2021 in part because she felt under pressure from the Green Party Executive to be less outspoken in support of trans rights than she wanted to be. Although I agree with her on this issue, I think it’s probably for the best that there is pressure to speak for a consensus, as opposed to Reform UK where the leader can make factually untrue statements about disabled people seemingly off the cuff without censure.

Green Party policies are set by ordinary members. There is a complicated process of drafting and gaining a minimum level of support for each policy, then placing proposals in order, which impacts which policies members at conference will have time to vote on. One of my lasting memories from the first time I attended Green Party conference in Autumn 2014 was Natalie Bennett, re-elected as leader earlier that day, standing as an ordinary member to propose a new policy. I can’t remember the details of the policy, but this sense of relatively radical egalitarianism is something that makes me proud to be a Green. Of course the process can be long and tedious, with hours set aside on each of the three days of conference to debate a new policy or internal process, with arguments for and against along with procedural motions and points of order taken from the floor. By contrast, Reform UK’s conference devoted just half an hour on Saturday to three motions which would then be discussed by the party board, making their internal democracy largely ceremonial.

That’s not to say that the spirit of equality is always followed. My memory is that, as co-leaders, Caroline Lucas and Jonathan Bartley spoke to the media in support of a 4-day week before it became party policy. In cases like this, the leader(s) should get the policy passed first, or at least make clear that it’s merely a proposed policy they are supporting, as is the case with Zack Polanski’s support for a motion which argues the Green Party should support leaving NATO, which seems to be a reversion to something like the policy held up until two and a half years ago – a broader, clearer opposition to NATO rather than the current conditional opposition which replaced it. The principle of the bully pulpit of course applies to the passing of new policies – any argument made by the party leader or other prominent members will be more widely heard and supported than the policy would otherwise.

A key role of a leader is to promote the party via the media, and there is clearly a media bias against the Green Party. Question Time hosted 15 UKIP representatives 63 times between May 2010 and February 2018, whereas 3 Green representatives appeared a total of 18 times. A graphic often circulated on social media shows that Question Time hosted 35 UK MEPs between January 2013 and February 2018, with only the Eurosceptic Tory Daniel Hannan representing a party other than UKIP, and the three Green MEPs being overlooked entirely. It’s possible to argue that the stupidity of UKIP got them a lot of their media attention. This was a political party where one MEP said that a meeting was “full of sluts”, another failed to become leader because of submitting his paperwork too late, and a third MEP hospitalised the second. But political media should aspire to inform, not merely chase views and clicks.

Whatever the reasons for the media bias, it has clearly existed. For the Green Party of England and Wales, the response has largely been to shift focus to the grassroots. The first version of the current campaigning manual was written in 2014, outlining a process known to members as ‘Target to Win’. Among other things, this process emphasises the importance of building connections as individual candidates, and being visible in the community. It took a while for the shift to start to pay off, but the total number of Green councillors grew from 198 in 2018 to 896 in 2025. Between 2018 and 2024 that’s an increase of between 77 and 204 seats each year, or between 10% to 90% year-on-year for six election years in a row. The obvious comparison is Reform UK’s 677 new councillors in 2025. While Greens have never had a single year with as many gains, the growth has been sustained. Given that within the first four months 7 of Reform UK’s new representatives have resigned as councillors, 2 have left the party, and 5 have been suspended or expelled (14 in total, or 2% of May’s intake), it’s likely the group as a whole will damage the party’s reputation and reduce the number of councillors re-elected when the same seats come up for re-election in 2029. Reform voters have voted for the idea of having a Reform councillor, Green voters, having done the same, have backed the party again knowing the reality of what it means to have a Green councillor.

2025 was the slowest year for Green growth since 2018, with 47 new councillors, less than 6% growth. There are multiple possible reasons for this, Reform UK’s success among them. Although it might seem counter-intuitive, I have spoken to voters who had decided not to vote for Labour or Tories but were open to anyone else, I’ve seen multiple ballots at counts who voted Green and UKIP. There was a well-reported trend in the 2016 election of voters who supported Bernie Sanders in primaries voted for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton, rejecting the status quo and open to anything else.

But it’s also worth considering that the Green growth based on community organising is very energy intensive. There are 339 councils in England and Wales, meaning that the 68,500 members work out to just over 200 members per council area. A lot of members don’t have the time to actively volunteer, and turnout in this year’s leadership election was roughly 35%, suggesting a lot of members who aren’t actively engaged. Without a sudden increase in membership, the Green Party may be reaching the point where a low-key campaign strategy will have diminishing results.

For this reason, in the 2021 leadership contest I considered voting for Amelia Womack and Tamsin Osmond, whose appeal was similar to Polanski’s. After weighing up the options I decided to vote for Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay for two main reasons – both Womack and Osmond lacked experience as elected regulators passing and in scrutinising policies; and with Denyer and Ramsay selected as target candidates for seats the Green Party believed could be won in 2024, it would look like a lack of faith to remove them as leaders. Polanski’s proposal that the leader should put more emphasis on building a mass movement is similar to Womack and Osmond’s, but he has been a London Assembly Member since 2021, chairing Environmental and Fire committees.

That doesn’t mean that I want or expect the 4 Green MPs to be low-key. During Natalie Bennett’s leadership from 2012 to 2016 Caroline Lucas was as visible in the media spotlight, if not more visible, and I’m hoping the same will happen with the 4 MPs. But ‘leadership’ has many forms, and by dividing the workload of communicator and legislator we as a party can give individual duties to the people who are best able to perform that duty well. Essentially it would be a model of leadership where Polanski will man the bully pulpit, and the MPs and councillors being the careful and innovative legislators. With Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana set to form a new left-wing party in the next year, the Green Party will need to make the case that our politicians and proposals are better equipped to improve the lives of ordinary people. It will be the first time in decades where more than one left-wing party will be competitive in more than a handful of seats in England and Wales.

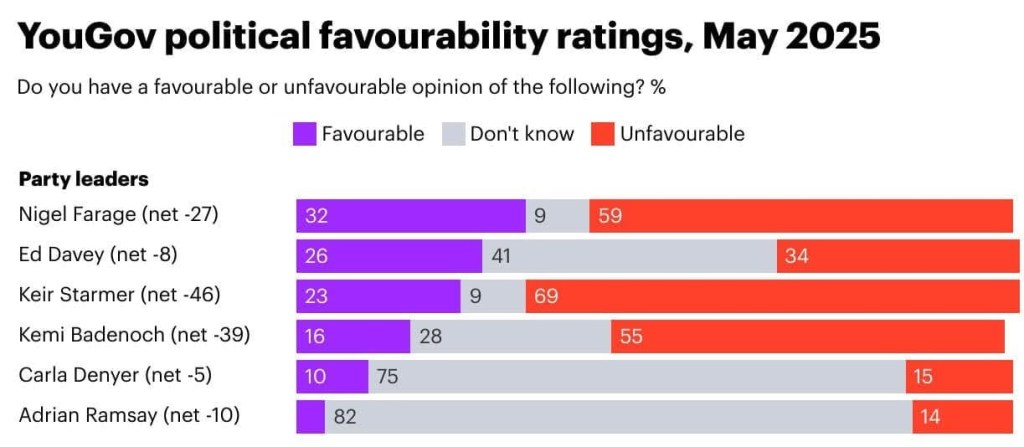

In May this year YouGov polling revealed that 4% of the public have a positive opinion of Adrian Ramsay, with 82% responding that they don’t know. Despite being the more active of the Co-Leaders in the media, Carla Denyer prompted a positive opinion in just 10% of respondents, with 75% not knowing. In many ways the pair are excellent politicians. As a councillor, in 2018 Denyer put forward a motion declaring a Climate Emergency, meaning that all other policies and actions must take the urgency into consideration. It’s a motion which had been copied by 307 more councils by November 2021. Outside of politics Adrian Ramsay has been chief executive of two different companies developing and demonstrating renewable energy, and he literally co-wrote the manual which has guided Green growth at council level in the past decade. During her first year as an MP, Ellie Chowns has been a tireless advocate for causes as diverse as social care, Fair Elections, Water Pollution, drawing on her PhD, which was examining the efficiency of the Malawi water sector.

In short the previous and rejected Green leadership are hard-working, innovative nerds, people who will dedicate themselves tirelessly to improving the lives of ordinary people. But to be able to do that, they need to be able to keep their seats and get more allies elected to support them, which I believe Zack Polanski is best placed to do. I have doubts about Polanski, most notably that he was still a member of the Liberal Democrats after their coalition years, speaking at their conference in 2015 aged 32. But he’s not the only Green leader to have started his political journey at a more right-wing party – Jonathan Bartley began his political career as a researcher for John Major, before his experience caring for his disabled son taught him about the injustices and negligence of the UK’s social safety nets.

More than in any other major British political party, holding power in the Green Party is collaborative and temporary. The quote from George Monbiot in the splash image at the top of the page is taken from an article written by Principle Speaker Derek Wall in 2007, which Wall quoted as part of his argument against shifting to a more traditional leadership model. Chowns and Ramsay have argued that Polanski’s election would represent an abandonment of a process that has delivered quickly increasing numbers of councillors, but I would argue that the change in approach will pour more resources into the current process – more members, more donations, and more voters who are well-informed about Green Party policy before the first volunteer knocks on their door. The success or failure of the Green Party of England and Wales will not be down to the actions of one man. It will be reliant on serious, hardworking MPs and councillors developing and implementing policies, doing the boring, quiet work of scrutinising formal reports and asking difficult technical questions of those with more power.

Leave a comment