Back in 2015 I played a small part in a campaign to oppose the slow closure of Hartlepool’s hospital. I played no significant organisational role in the ‘Save our Hospital’ campaign but attended a few events, meetings and online discussions. One common argument that recurred was that the campaign “shouldn’t be about politics”.

As part of this school of thought Stephen Picton, a local taxi driver and charity fundraiser, stood in the 2015 general election to be the town’s MP, the idea being that the election of someone not in thrall to any political party would be the best way to protect the University Hospital of Hartlepool. It wasn’t totally unreasonable as an aim – Hartlepool is the town that once elected a football mascot as mayor, so there is a decent level of anti-establishment feeling to the town’s politics. Like a lot of voters I wasn’t a fan of the incumbent Labour MP Iain Wright but I felt sure that he would be a better choice to represent the town and look after local health services than Picton, as he simply had more understanding of how the relevant political systems work.

I can understand the anti-politics sentiment, and I sympathise with it. Politics has a terrible reputation – most people associate the term with the often amoral quest for power, manipulating and sidelining the truth in order to access power and money. But there are plenty of political actions carried out purely for principle. As an example of a politician acting out of principle directly against their own self-interest, I’ll look to David Cameron.

In 2004 the Civil Partnership Act was passed by a Labour government, conferring many of the benefits and responsibilities of marriage, but framed in such a way that many gay couples didn’t have their foreign marriages recognised by UK law.

The opposition to the bill within the Tory Party was clear in advance – a highly publicised letter from local party chairs claimed that there was huge concern at the grasroots, and that members were leaving “in their droves” because of David Cameron’s belief that gay couples should have equal rights to their straight counterparts.

On the whole I’m certainly no fan of David Cameron. In my view his policies directly increased the amount of poverty in our nation. After promising to put an end to top-down reorganisation of the NHS he implemented probably the biggest ever top-down reorganisation of the NHS. His rushed Brexit vote (not allowing time for thorough debate) will make the country poorer while probably ushering in the end of the UK in its current form. But it’s common to represent politicians as entirely without principle, and I would consider that to rarely be the case.

As it’s possible to recognise principle in people that I dislike, it’s also possible to recognise principles that we dislike. In 2015 I was campaigning for the Green Party, and attended a few hustings debates, mostly between the candidates for Stockton South. The UKIP candidate for this election was a man named Ted Strike, who had stood for the Christian Party in the same seat in 2010.

If my memory is correct he mentioned that he first got involved in politics to oppose part of the sex education lessons introduced by the Labour government, I think relating to homosexuality. I disagreed with him on this – my belief is that adolescents should be given the knowledge to understand the changes happening to them before they go through puberty. He struck me as fitting the archetype of a politically opinionated but old-fashioned pub landlord – not someone I would want to hold any position of serious power but someone doing what he thinks is best based on his outdated view of the world. I was previously aware of him for an infamous Facebook post where he wondered if storms were God’s divine punishment for the gay marriage law, so I didn’t have a high opinion of him. But attending those debates I saw someone who was not hateful, but a broadly decent man with some very outdated and strange views.

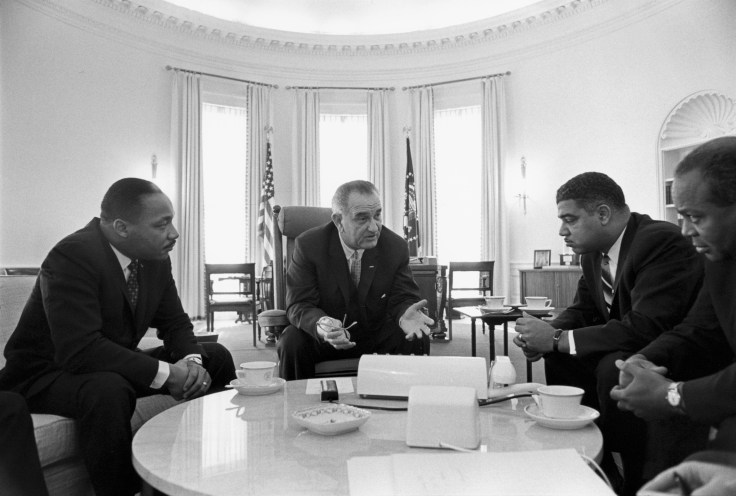

A more obvious example of political idealism is Doctor Martin Luther King, who stood against the mistreatment of black men and women in America over the course of decades. But it wasn’t enough that he opposed injustice – he used public pressure and shame to build support among the public. For a variety of reasons, ranging from outright racism to having other priorities, legislators of Dr King’s time were not generally in favour of changing laws to give black Americans equal treatment. Change didn’t come just because King had a dream in his head and on his tongue. He used public protests – ranging from the Montgommery bus boycott to the March on Washington – to empower downtrodden black people and to force white people to think about the injustice around them. While these were good aims in their own right, they also had the effect of pressurising public officials, of making a minor issue into a priority. The reality of politics is that asking nicely often isn’t enough, politics is also the art of applying pressure to achieve our aims.

In political discussions it’s important to think about who holds power. This doesn’t need to be formal political power – during the 1980s Arthur Scargill was thought of as being one of the most powerful people in the country, because of his position and reputation among unions. Jacob Rees-Mogg is arguably more powerful than Theresa May right now, because of his pro-Brexit connections and ability to play to the pro-Brexit crowd, while May is penned in under pressure to complete an impossible task.

In a 2015 debate Donald Trump made a rare display of the honesty that his supporters turn to him for, saying that he has donated to politicians of both major parties as

On a similar note, when we get annoyed at co-workers for playing ‘office politics’ it’ll generally mean that rather than focusing on their work, they put effort into building alliances, building a friendship with the boss as an investment for when promotions and business trips become available. ‘Office politics’ rarely has anything to do with voting.

Politics is the art of advancing causes, but also the art of individuals advancing themselves. Politics can be noble and far-sighted, or base and self-centred. It’s often tempting to overlook the complexity represented by that single word.

Should we elect people who know how our political systems work, or people we trust?

Should we give credit to politicians we disagree with when they make a principled stand that goes against their allies?

Should we give credit when politicians make unpopular stands to advance principles that we disagree with?

How important is strategy alongside political principle?

What does ‘office politics’ mean?

Leave a comment